Healing the Wild, Inside and Out

Jessie Bunkley

Preserve Steward, Seawood Cape Preserve

For ten days in late July and early August, the air at Seawood Cape Preserve was filled not only with the usual sounds of crashing waves, birdsong, and rustling leaves but also with the giggles, chattering, and bantering of 11 young people visiting the north coast to help heal the land and, in doing so, hopefully, find nourishment themselves.

Preserve Stewards Jessie and Tim welcome the Outward Bound Adventure crew. Photo by Dulce Real.

The Preserve welcomed the group of youth from Outward Bound Adventures, a high-school program based in Pasadena, CA, to camp on the Preserve and join us as stewards. For several participants, this was their first experience camping, and while the news of a refrigerator and water heater for showers was a relief, the update about recent bear activity caused some unease. Their first lesson as stewards was that we share this place with numerous other creatures and respect is the key to coexistence. That night, the group set up their tents and unrolled their sleeping bags under a clear sky between redwood, spruce, and fir trees.

Over the coming days, new leather gloves were broken in, vocabularies expanded to include words like chyer'ery' (Yurok for black bear) and puuek (black-tailed deer), tongues tasted ripe salmon berries and huckleberries for the first time, and parts of the preserve began to change.

Litter was picked up along the roadsides, areas of the forest were thinned, and invasive plants, like Portuguese heath and English ivy, were removed from large swaths of meadow and forest. While pulling ivy next to one young man, we discussed his plans for the future. He is enrolled in a nursing program at a community college this fall. It will involve a fair amount of commuting, but is a good program and the credits will transfer to a UC or Cal State school. We pulled up ivy by the roots and rolled it like a carpet down the hill. Then, we worked our way in the other direction on the steep slope, pulling, rolling, and cutting the stubborn vines. The result was a pile of ivy over three feet tall and six feet across. Huffing from exertion, we both collapsed into the ivy bean bag chair for a water break.

The crew set up their tents, some for the first time. Photo by Caitlin Jane “CJ” Calica.

Our conversation turned biological as we mused about plants — photosynthesis, chlorophyll, fungal networks that allow nutrients to pass between individuals — and then philosophical as we ventured into the wonder of it all and our ability to perceive and appreciate the world around us. What a gift!

We talked about the organisms in the intertidal, slugs, and trees. How did they perceive the world? What were their life experiences like? We discussed how this small act of pulling the invasive vine, challenging though it was, might compound on others to help restore balance to the land and how such actions multiplied by the millions might redirect our current trajectory of ecological disaster. In that conversation, we saw one another as we are: creatures part of an ecosystem with a desire to make it better.

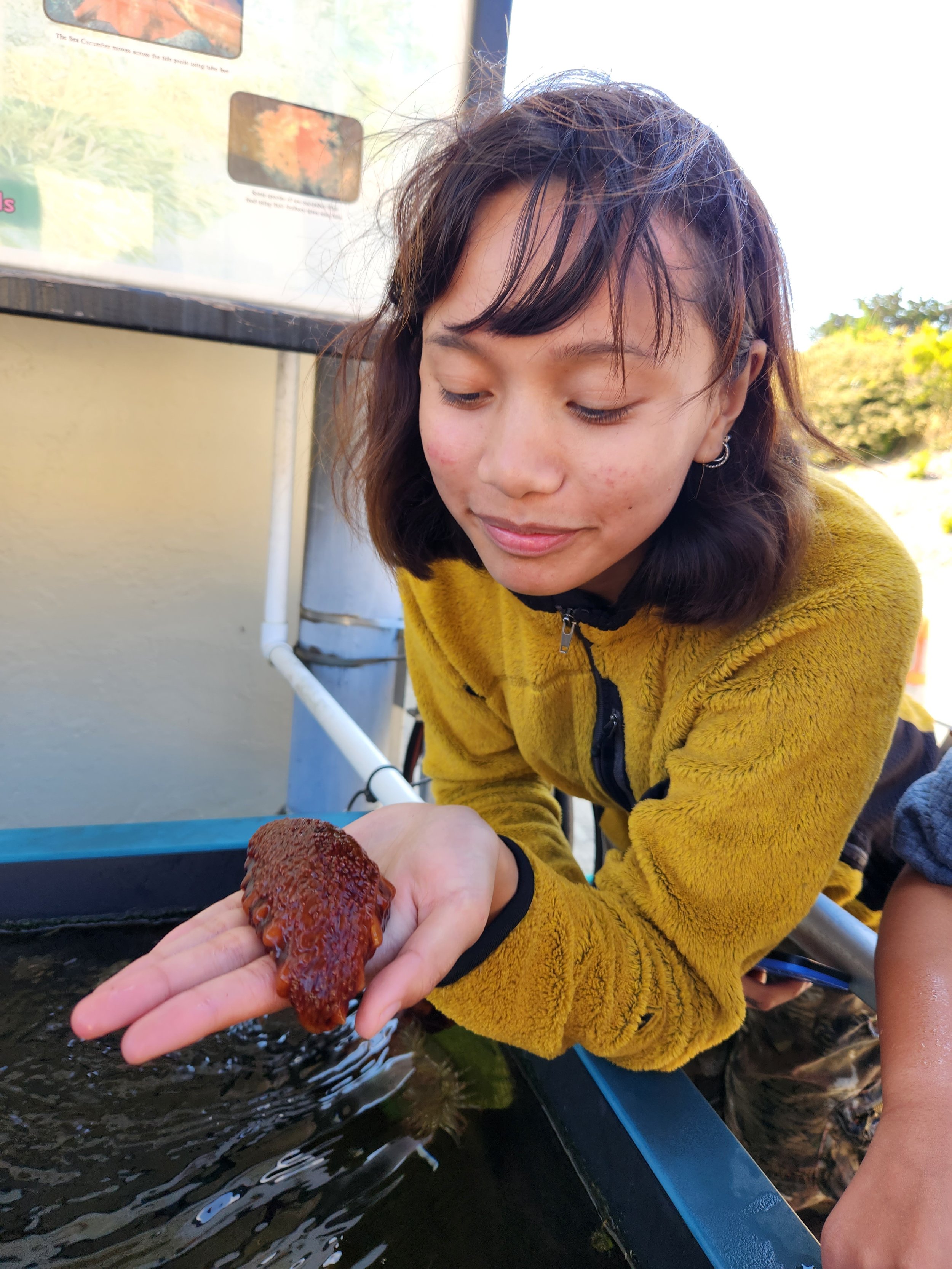

The group worked daily from 8 am to 2 pm; afterward, they explored the community, visiting ancient redwood groves, spending thoughtful moments in the shelter of a Yurok house at Sue-Meg State Park, meeting the fascinating intertidal creatures at the Telonicher Marine Lab touch-tank, swimming at Moonstone Beach, and viewing the world as a canopy-dwelling wandering salamander does, from the Sequoia Park Zoo’s redwood skywalk. All the while, they learned about and became part of a place vastly different from their homes.

As we pulled heath in the wet meadow, I discovered that the three group leaders also maintained full-time jobs. On the final night of their visit, after s’mores were eaten and the fire was slowly dying, I asked Dulce, one of the trip leaders, about how she became involved in Outward Bound Adventures.

Dulce described growing up in Los Angeles, a city cut off from nature, and of her first experience at a National Park when she watched a spectacular sunset in Death Valley with her cousin and wondered why she had never been there before. She soon found community with people doing trail stewardship work, and when a friend told her about an opportunity to participate in the Outward Bound Adventures’ Diverse Outdoor Leaders Institute, she applied. She was accepted to do the training and, at 19, became the youngest in her cohort.

Seven years later, she continues this important work, shepherding a group of 15-to 18-year-olds into their journey discovering the wilderness, sharing those awe-striking moments of seeing a massive redwood for the first time, looking out across Yosemite Valley, touching the soft, leathery skin of a bat star. These are special experiences at a formative time for young people whose lives typically unfold in a cityscape. She described the ‘heart work’ of encouraging them to dream big and not let anyone constrain the futures they see for themselves, the importance of community and being welcomed to explore new spaces that are often reserved for only a few, and of the curiosity and bravery necessary for that exploration.

The Wildlands Conservancy has partnered with Outward Bound Adventures for a number of years, hosting groups across the preserve system. Every year at Seawood Cape Preserve, they build on the work of the previous years’ team, leaving their mark in the form of a new patch of redwood violets growing in a sunny spot that was once shaded by too many grand firs, or as a tadpole in a new puddle that was able to form in the wet meadow where heath once stood thick. We hope their time on the Preserve has left a mark on them as well, an understanding that this world is all of ours, from bat star to candy flower, and that as stewards, we are all responsible for its health and protection. This is the heart work we all need to do.

After 10 days of stewarding, learning and exploring, the changes are visible in both land and people. Photos: Gloria Rosales and Julio Sandoval